The authoritative version is published in DiGRA 2025 conference proceedings https://doi.org/10.26503/dl.v2025i2.2461

Petri Lankoski (Södertörn University, Sweden) & Tanja Välisalo (University of Jyväskylä, Finland)

ABSTRACT

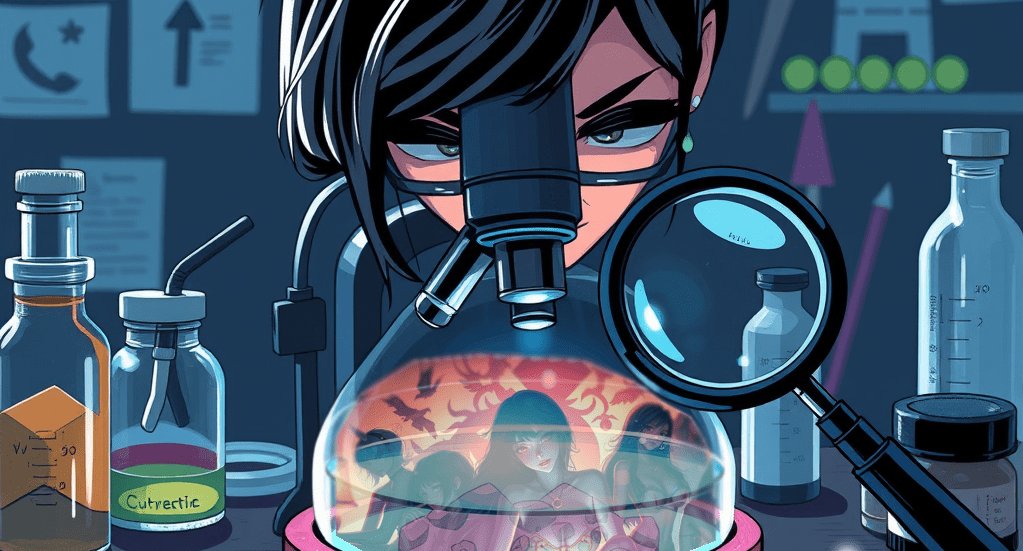

Parties and partying appear in single-player videogames but have been studied little. In this paper, we investigate how parties are used and represented in videogames. In this explorative study, we analyzed 22 games to answer the research question. Parties in games are often intertextual references to film and television as well as to party games in popular culture. The analysis resulted in the following themes: Party as a Backdrop, Party as Space for Social Interaction, Party as a Place to Have Sex (with subthemes Bodies Collide, Party Games as Minigames and Party Games Motivating Sexual Encounters), Party as a Place for Voyeurism, and Organising a Party as a Challenge.

Keywords

parties, party games, intertextuality, videogames

Continue reading “Parties, partying, and party games in single-player videogames”